|

History from 1350 AD 1350 to 1550 The Merchants and the City/States

|

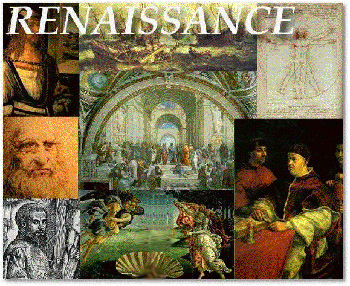

To them, this marked a new age, which historians later called the Renaissance (French for

"rebirth") and viewed as a distinct period of European history, which began in Italy and

then spread to the rest of Europe.

Renaissance Italy was largely an urban society. The city-states became the centers of

Italian political, economic, and social life.

Within this new urban society, a secular spirit emerged as increasing wealth created new

possibilities for the enjoyment of worldly things.

The Renaissance was also an age of recovery from the disasters of the fourteenth century,

including the Black Death, political disorder, and economic recession.

In pursuing that recovery, Italian intellectuals became intensely interested in the

glories of their own past, the Greco-Roman culture of antiquity.

A new view of human beings emerged as people in the Italian Renaissance began to emphasize

individual ability.

The fifteenth-century Florentine architect Leon Battista Alberti expressed the new

philosophy succinctly: "Men can do all things if they will." This high regard for human

worth and for individual potentiality gave rise to a new social ideal of the well-rounded

personality or "universal person" who was capable of achievements in many areas of life.

The emergence and growth of individualism and secularism as characteristics of the Italian

Renaissance are most noticeable in the intellectual and artistic realm.

The most important literary movement associated with the Renaissance is humanism.

Renaissance humanism was an intellectual movement based on the study of the classics, the

literary works of Greece and Rome. Humanists studied the the liberal works - grammar,

rhetoric, poetry, moral philosophy or ethics, and history - all based on the writings of

ancient Greek and Roman authors. We call these subjects the humanities.

Petrarch (1304 - 1374), who has often been called the father of Italian Renaissance

humanism, did more than any other individual in the fourteenth century to foster its

development. Petrarch sought to find forgotten Latin manuscripts and set in motion a

ransacking of monastic libraries throughout Europe.

He also began the humanist emphasis on the use of pure classical Latin. Humanists used

the works of Cicero as a model for prose and those of Virgil for poetry. As Petrarch

said, "Christ is my God; Cicero is the prince of the language."

The European empires of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries rested on a mastery of the

oceans.

This mastery was partly the product of long experience in Atlantic waters. For example,

the Portuguese caravel - the workhorse ship of the fifteenth-century voyages to Africa -

was based on ship and sail designs that had been in use among Portuguese fishermen since

the thirteenth century.

Starting in the 1440's, however, Portuguese shipwrights began building larger caravels of

about fifty tons displacement, with two masts each carrying a triangular sail. Such ships

were capable of sailing against the wind much more effectively than were the older,

square-rigged vessels.

They also required much smaller crews than did the multi-oared galleys that were still

commonly used in the Mediterranean.

By the end of the fifteenth century, even larger caravels of around two hundred tons were

being constructed, with a third mast and a combination of square and lateen rigging.

Columbus's Nina was of this design, having been refitted with two square sails in the

Canary Islands to enable it to sail more efficiently before the wind during the Atlantic

crossing.

Europeans were also making significant advances in navigation during the fifteenth and

sixteenth centuries. Quadrants, which calculated latitude in the Northern hemisphere by

the height above the horizon of the North Star, were in widespread use by the 1450s.

As sailors approached the equator, however, the quadrant became less and less useful, and

they were forced instead to make use of astrolabes, which reckoned latitude by the height

of the sun. It was not until the 1480s that the astrolabe became a really useful

instrument for seaborne navigation, with the preparation of standard tables sponsored by

the Portuguese crown.

Compasses too were also coming into more widespread use during the fifteenth century.

Longitude, however, remained impossible to calculate accurately until the eighteenth

century, when the invention of the marine chronometer finally made it possible to keep

accurate time at sea.

In the sixteenth century, Europeans sailing east or west across the oceans generally had

to rely on their skill at dead reckoning to determine where they were on the globe.

European sailors also benefited from a new interest in maps and navigational charts.

Especially important to Atlantic sailors were books known as rutters or routiers.

These contained detailed sailing instructions and descriptions of the coastal landmarks a

pilot could expect to encounter on route to a variety of destinations.

Mediterranean sailors had had similar books, known as portolani, since at least the

fourteenth century. In the fifteenth century, however, this tradition was extended to the

Atlantic Ocean; by the end of the sixteenth century, rutters spanned the globe.

The Renaissance witnessed the development of printing, which made an immediate impact on

European intellectual life and thought. Printing from hand-carved wooden blocks had been

done in the West since the twelfth century and in China even before that.

What was new in the fifteenth century in Europe was multiple printing with movable metal

type.

The development of printing from movable type was a gradual process that culminated some

time between 1445 and 1450; Johannes Gutenberg of Mainz played an important role in

bringing the process to completion. Gutenberg's Bible, completed in 1455 or 1456, was the

first true book produced from movable type.

By 1500, there were more than a thousand printers in Europe, who collectively had

published almost forty thousand titles (between eight and ten million copies).

Probably 50 percent of these books were religious - Bibles and biblical commentaries,

books of devotion, and sermons.

Next in importance were the Latin and Greek classics, medieval grammars, legal handbooks,

and works on philosophy.

The printing of books encouraged the development of scholarly research and the desire to

attain knowledge.

Printing also stimulated the development of an ever-expanding lay reading public, a

development that had an enormous impact on European society.

Printing allowed European civilization to compete for the first time with the civilization

of China.

The Protestant Reformation is the name given to the religious reform movement that divided

the western church into Catholic and Protestant groups.

Although Martin Luther began the Reformation in the early sixteenth century, several

earlier developments had set the stage for religious change.

During the second half of the fifteenth century, the new classical learning of the Italian

Renaissance spread to the European countries north of the Alps and spawned a movement

called Christian humanism or Northern Renaissance humanism, whose major goal was the

reform of Christendom.

The Christian humanists believed in the ability of human beings to reason and improve

themselves and thought that through education in the sources of classical, and especially

Christian, antiquity, they could instill an inner piety or an inward religious feeling

that would bring about a reform of the church and society.

To change society, they must first change the human beings who compose it.

While the leaders of the church were failing to meet their responsibilities, ordinary

people were clamoring for meaningful religious expression and certainty of salvation.

As a result, for some the process of salvation became almost mechanical. Collections of

relics grew as more and more people sought certainty of salvation through veneration of

these relics.

Frederick the Wise, elector of Saxony and Martin Luther's prince, had amassed over five

thousand relics to which were attached indulgences that could reduce one's time in

purgatory by 1,443 years. (An indulgence is a remission, after death, of all or part of

the punishment due to sin.)

Martin Luther was a monk and a professor at the University of Wittenberg, where he

lectured on the Bible. Probably sometime between 1513 and 1516, through his study of the

Bible, he arrived at an answer to a problem - the assurance of salvation - that had

disturbed him since his entry into the monastery.

Luther did not see himself as a rebel, but he was greatly upset by the widespread selling

of indulgences.

Especially offensive in his eyes was the monk Johann Tetzel, who hawked indulgences with

the slogan: "As soon as the coin in the coffer (money box) rings, the soul from purgatory

springs."

Greatly angered, he issued in 1517 a stunning indictment of the abuses in the sale of

indulgences, the Ninety-Five Theses. Thousands of copies were printed and quickly spread

to all parts of Germany.

Between 500 and 1500, the level of interdependence among human societies began to

intensify as three major trade routes - the Indian Ocean, the Silk Road, and the

trans-Saharan caravan route - began to create the framework for a single world trade

system. New technology, new crops, and new ideas crossed from one end of the known world

to the other.

Contacts occurred in the realm of technology as in that of ideas, including inventions

such as paper, the compass, and gunpowder; crops such as sugar, cotton, and spices; and

great religious systems such as Buddhism, Hinduism, Christianity, and Islam.

One interesting aspect of this process was the close relationship between missionary

activities and trade. Buddhist merchants first brought the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama

to China, and Muslim traders carried the words of the prophet Muhammad to Southeast Asia

and sub-Saharan Africa.

At the same time, Christian missionaries may have brought the first accurate knowledge of

silk manufacturing from China t the Mediterranean.

What were the major causes of the rapid expansion of trade during this period?

One key factor was the introduction of new technology in the field of transportation.

The development of the compass, improved techniques in map-making and shipbuilding, and

greater knowledge of wind patterns all contributed to the expansion of maritime trade far

from familiar shores.

Caravan trade, once carried by wheeled chariots or on the backs of oxen, now used the

camel as the preferred beast of burden through the parched deserts of Africa and the

Middle East.

But the Middle East was not the only or necessarily even the primary contributor to world

trade and civilization during this period.

While the Arab Empire became the linchpin of trade between the Mediterranean and eastern

and southern Asia, a new center of primary importance in world trade was emerging in East

Asia, focused on China. China had been a major participant in regional trade during the

Han dynasty, when its silks were already being transported to Rome via Central Asia, but

its role had declined after the fall of the Han.

Now, with the rise of the great Tang and Song dynasties, China reemerged as a major

commercial power in East Asia, trading by sea with Southeast Asia and Japan and by land

with the nomadic peoples of Central Asia. In general, overland trade was carried on by

non-Chinese peoples in Central Asia, but the Chinese themselves became directly involved

in the maritime trade with the countries in the South Seas.

By now, China was not only a regional economic power but a global one as well. The Silk

Road through Turkestan became one of the most important trade routes of the era, and

during the Ming dynasty, Chinese fleets briefly sailed across the Indian Ocean as far as

the Red Sea and the eastern coast of Africa.

Like the Middle East, China was also a prime source of new technology. From China came

paper, printing, the compass, and gunpowder.

The double-hulled Chinese junks that entered the Indian Ocean during the Ming dynasty were

slow and cumbersome but extremely seaworthy and capable of carrying substantial quantities

of goods over long distances.

Among China's other contributions were porcelain, chess, the mechanical clock, and the

iron stirrup. Many such inventions arrived in Europe by way of India or the Middle East,

and their Chinese origins were therefore unknown in the West.

Increasing trade on a regional or global basis also led to the exchange of ideas.

Buddhism was brought to China by merchants, and Islam first arrived in sub-Saharan Africa

and the Indonesian archipelago in the same manner.

In their new environments, these religions initially had an impact mainly on merchants and

other city-dwellers, but in some cases they gradually gained favor in the countryside.

In the early centuries of Chinese civilization, the bulk of the population had been

located along the Yellow River.

Smaller settlements were located along the Yangtze and in the mountainous regions of the

south, but the administrative and economic center of gravity was clearly in the north.

By the Song period, however, that emphasis had already begun to shift drastically as a

result of climatic changes, deforestation, and continuing pressure from nomads in the Gobi

Desert.

By the early Qing, the economic breadbasket of China was located along the Yangtze River

or in the mountains to the south.

Moreover, the population was beginning to increase rapidly.

For centuries, China's population had remained within a range of 50 to 100 million, rising

in times of peace and prosperity and falling in periods of foreign invasion and internal

anarchy.

During the Ming and the early Qing, however, the population increased from an estimated 70

to 80 million in 1390 to over 300 million at the end of the eighteenth century. There

were probably several reasons for this population increase:

The relatively long period of peace and stability under the early Qing; the introduction

of new crops from the Americas, including peanuts, sweet potatoes, and maize; and the

planting of a new species of faster-growing rice from Southeast Asia.

Qing Dynasty

This population increase meant much greater pressure on the land, smaller farms, and a

razor-thin margin of safety in case of climatic disaster.

The imperial court attempted to deal with the problem through a variety of means, most

notably by preventing the concentration of land in the hands of wealthy landowners.

Nevertheless, by the eighteenth century, almost all land that could be irrigated was

already under cultivation, and the problems of rural hunger and landlessness became

increasingly serious.

As in earlier periods, Chinese society was organized around the family. Before, the ideal

family unit in Qing China was the joint family, in which as many as three or even four

generations lived under the same roof.

When sons married, they brought their wives to live with them in the family homestead.

Prosperous families would add a separate section to the house to accommodate the new

family. Unmarried daughters would also remain in the house.

Aging parents and grandparents remained under the same roof until they died and were

cared for by younger members of the household.

The family retained its importance in early Qing times for much the same reasons as in

earlier times.

As a labor-intensive society based primarily on the cultivation of rice, China needed

large families to help with the harvest and to provide security for parents too old to

work in the fields.

Sons were particularly prized, not only because they had strong backs but also because

they would raise their own families under the parental roof.

With few opportunities for employment outside the family, sons had little choice but to

remain with their parents and help on the land.

Within the family, the oldest male was king, and his wishes theoretically had to be obeyed

by all family members.

For many Chinese, the effects of these values were most apparent in the choice of a

marriage partner.

Marriages were normally arranged for the benefit of the family, often by a go-between, and

the groom and bride were usually not consulted.

Frequently, they did not meet until the marriage ceremony.

Under such conditions, love was clearly a secondary consideration. In fact, it was often

viewed as detrimental, since it inevitably distracted the attention of the husband and

wife from their primary responsibility to the larger family unit.

In traditional China, the role of women had always been inferior to that of men.

A sixteenth-century Spanish visitor to South China observed that Chinese women were "very

secluded and virtuous, and it was a very rare thing for us to see a woman in the cities

and large towns, unless it was an old crone."

Women were more visible, he said, in rural areas, where they frequently could be seen

working in the fields.

The concept of female inferiority had deep roots in Chinese history.

This view was embodied in the belief that only a male would carry on sacred family

rituals and that men alone had the talent to govern others.

Only males could aspire to a career in government or scholarship. Within the family

system, the wife was clearly subordinated to the husband. Legally, she could not divorce

her husband or inherit property.

The husband, however, could divorce his wife if she did not produce male heirs, or he

could take a second wife as well as a concubine for his pleasure.

A widow suffered specially, because she had to either raise her children on a single

income or fight off her former husband's greedy relatives, who would coerce her to remarry

since, according to the law they would then inherit all of her previous property and her

original dowry.

Female children were less desirable because of their limited physical strength and because

their parents would be required to pay a dowry to the parents of their future husband

Female children normally did not receive an education, and in times of scarcity when food

was in short supply, daughters might even be put to death.

At the end of the fifteenth century, the traditional Japanese system was at a point of

near anarchy. With the decline in the authority of the Ashikaga shogunate at Kyoto, clan

rivalries had exploded into an era of warring states similar to the period of the same

name in Zhou dynasty China.

Even at the local level, power was frequently diffuse.

The typical daimyo (great lord) domain had often become little more than a coalition of

fief-holders held together by a loose allegiance to the manor lord. Prince Shotoku's

dream of a united Japan appeared to be only a distant memory.

In actuality, Japan was on the verge of an extended era of national unification and peace

under the rule of its greatest shogunate, the Tokugawa.

The unification of Japan took place almost simultaneously with the coming of the

Europeans.

Portuguese traders sailing in a Chinese junk that may have been blown off course by a

typhoon had landed on the islands in 1543.

Within a few years, Portuguese ships were stopping at Japanese ports on a regular basis to

take part in the regional trade between Japan, China, and Southeast Asia.

The first Jesuit missionary, Francis Xavier, arrived in 1549.

The curious Japanese were fascinated by tobacco, clocks, spectacles, and other European

goods, and local daimyo (feudal landowners) were interested in purchasing all types of

European weapons and armaments.

Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi found the new firearms helpful in defeating their

enemies and unifying the islands.

The effect on Japanese military architecture was particularly striking as local lords

began to erect castles on the European model.

Many of these castles, such as Hideyoshi's castle at Osaka, still exist today.

The missionaries also had some success.

They converted a number of local daimyo, some of whom may have been motivated in part by

the desire for commercial profits.

By the end of the sixteenth century, thousands of Japanese in the southernmost islands of

Kyushu and Sikoku had become Christians.

One converted daimyo ceded the superb natural harbor of the modern city of Nagasaki to the

Society of Jesus, which proceeded to use the new settlement for both missionary and

trading purposes.

But papal claims to the loyalty of all Japanese Christians and the European habit of

intervening in local politics soon began to arouse suspicion in official circles.

Missionaries added to the problem by deliberately destroying local idols and shrines and

turning some temples into Christian schools or churches.

Inevitably, the local authorities reacted. In 1587, Toyotomi Hideyoshi issued an edict

prohibiting further Christian activities within his domains. Japan, he declared, was "the

land of the Gods," and the destruction of shrines by the foreigners was "something unheard

of in previous ages."

To "corrupt and stir up the lower classes" to commit such sacrileges, he declared, was

"outrageous." The parties responsible (the Jesuits) were ordered to leave the country

within twenty days.

Hideyoshi was careful to distinguish missionary from trading activities, however, and

merchants were permitted to continue their operations.

The long period of peace under the Tokugawa shogunate made possible a dramatic rise in

commerce and manufacturing, especially in the growing cities.

By the mid-eighteenth century, Edo, with a population of more than one million, was one of

the largest cities in the world. The growth of trade and industry was stimulated by a

rising standard of living - driven in part by technological advances in agriculture and an

expansion of arable land.

The Daimyo's need for income also contributed as many of them began to promote the sale of

local goods from their domains, such as textiles, forestry products, sugar, and sake.

Most of this commercial expansion took place in the major cities and the castle towns,

where the merchants and artisans lived along with the samurai, who were clustered in

neighborhoods surrounding the daimyo's castle.

Banking flourished and paper money became the normal medium of exchange in commercial

transaction.

Merchants formed guilds not only to control market conditions but also to facilitate

government control and the collection of taxes.

Under the benign if somewhat contemptuous supervision of Japan's noble rulers, a Japanese

merchant class gradually began to emerge from the shadows to play a significant role in

the life of the Japanese nation.

Some historians view the Tokugawa era as the first stage in the rise of an indigenous

form of capitalism, based loosely on the Western model.

In the late thirteenth century, a new group of Turks under the tribal leader Osman

(1280-1326) began to consolidate their power in the northwestern corner of the Anatolian

peninsula.

That land had been given to them by the Seljuk rulers as a reward for helping drive out

the Mongols in the late thirteenth century.

At first, the Osman Turks were relatively peaceful and engaged in pastoral pursuits, but

as the Seljuk empire began to disintegrate in the early fourteenth century, they began to

expand and founded the Osmanli (later to be known as Ottoman) dynasty.

A Key advantage for the Ottomans was their location in the northwestern corner of the

peninsula. From there they were able to expand westward and eventually control the

Bosporus and the Dardanelles, between the Mediterranean and the Black Seas.

The Byzantine Empire, of course, had controlled the area for centuries, serving as a

buffer between the Muslim Middle East and the Latin West.

The Byzantines, however, had been severely weakened by the sack of Constantinople in the

Fourth Crusade (in 1204) and the Western occupation of much of the empire for the next

half century.

In 1360, Orkhan was succeeded by his son Murad I, who consolidated Ottoman power in the

Balkans, set up a capital at Edirne (modern Adrianople), and gradually reduced the

Byzantine emperor to a vassal.

Murad did not initially attempt to conquer Constantinople because his forces were composed

mostly of the traditional Turkish cavalry and lacked the ability to breach the strong

walls of the city.

Instead, he began to build up a strong military administration based on the recruitment of

Christians into an elite guard.

Called Janissaries (from the Turkish yeni cheri, "new troops"), they were recruited from

the local Christian population in the Balkans and then converted to Islam and trained as

foot soldiers or administrators.

One of the major advantages of the Janissaries was that they were directly subordinated to

the sultanate and therefore owed their loyalty to the person of the sultan. Other

military forces were organized by the beys and were thus loyal to their local tribal

leaders.

The Janissary corps also represented a response to changes in warfare. As the knowledge

of firearms spread in the late fourteenth century, the Turks began to master the new

technology, including siege cannons and muskets.

The traditional nomadic cavalry charge was now outmoded and was superseded by infantry

forces armed with muskets. Thus the Janissaries provided a well-armed infantry who served

both as an elite guard to protect the palace and as a means of extending Turkish control

in the Balkans.

With his new forces, Murad defeated the Serbs at the famous Battle of Kosovo in 1389 and

ended Serbian hegemony in the area.

The last Byzantine emperor desperately called for help from the Europeans, but only the Genoese came to his defense.

With eighty thousand troops ranged against only seven thousand defenders, Mehmet laid

siege to Constantinople in 1453.

In their attack on the city, the Turks made use of massive cannons with 26-foot barrels

that could launch stone balls weighing up to 1,200 pounds each.

The Byzantines stretched heavy chains across the Golden Horn, the inlet that forms the

city's harbor, to prevent a naval attack from the north and prepared to make their final

stand behind the 13-mile-long wall along the western edge of the city.

But Mehmet's forces seized the tip of the peninsula north of the Golden Horn and then

dragged their ships overland across the peninsula from the Bosporus and put them into the

water behind the chains.

Finally, the walls were breached; the Byzantine emperor died in the final battle.

Mehmet II, standing before the palace of the emperor, paused to reflect on the passing

nature of human glory.

But it was not long before he and the Ottomans were again on the march.

With their new capital at Constantinople, renamed Istanbul, the Ottoman Turks had become a

dominant force in the Balkans and the Anatolian peninsula.

After their conquest of Constantinople in 1543, the Ottoman Turks tried to complete their

conquest of the Balkans, where they had been established since the fourteenth century.

Although they were successful in taking the Romanian territory of Wallachia in 1476, the

resistance of the Hungarians initially kept the Turks from advancing up the Danube

valley

.

From 1480 to 1520, internal problems and the need to consolidate their eastern frontiers

kept the Turks from any further attacks on Europe.

Suleyman I the Magnificent (1520 - 1566), however, brought the Turks back to Europe's

attention.

The Turks overran most of Hungary, moved into Austria, and advanced as far as Vienna,

where they were finally repulsed in 1529.

At the same time, they extended their power into the western Mediterranean and threatened

to turn it into a Turkish lake until a large Turkish fleet was destroyed by the Spanish at

Lepanto in 1571.

Although Europeans frequently called for new Christian Crusades against the "infidel"

Turks, the Ottoman Empire was, by the beginning of the seventeenth century, being treated

like any other European power by European rulers seeking alliances and trade concessions.

During the first half of the seventeenth century, the Ottoman Empire was a "sleeping

giant."

Involved in domestic bloodletting and heavily threatened by a challenge from Persia, the

Ottomans were content with the status quo in eastern Europe.

But under a new line of grand vezirs in the second half of the seventeenth century, the

Ottoman Empire again took the offensive.

By mid-1683, the Ottomans had marched through the Hungarian plain and laid siege to

Vienna,.

Repulsed by a mixed army of Austrians, Poles, Bavarians, and Saxons, the Turks retreated

and were pushed out of Hungary by a new European coalition.

Although they retained the core of their empire, the Ottoman Turks would never again be a

threat to Europe.

The Turkish empire held together for the rest of the seventeenth and the eighteenth

centuries, but it faced new challenges from the ever-growing Austrian Empire in

southeastern Europe and the new Russian giant to the north.

In retrospect, the period from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries can be viewed both as

a high point of traditional culture in India and as the first stage of perhaps its

greatest challenge.

The era began with the creation of one of the subcontinent's greatest empires, that of the

Mughals. Mughal rulers, although foreigners and Muslims, like many of their immediate

predecessors, nevertheless brought India to a peak of political power and cultural

achievement.

For the first time since the Mauryan dynasty, the entire subcontinent was united under a

single government, with a common culture that inspired admiration and envy throughout the

entire region.

The Mughals were the last of the great traditional Indian dynasties.

Like so many of their predecessors since the fall of the Guptas nearly a thousand years

before, the Mughals were Muslims.

But like the Ottoman Turks, the best Mughal rulers did not simply impose Islamic

institutions and beliefs on the predominantly Hindu population; they combined Muslim with

Hindu and even Persian concepts and cultural values in a unique social and cultural

synthesis that still today seems to epitomize the greatness of Indian civilization.

Women had traditionally played an active role in Mongol tribal society - many actually

fought on the battlefield alongside the men - and Babur and his successors often relied on

the women in their families for political advise.

Women from aristocratic families were often awarded honorific titles, received salaries,

and were permitted to own land and engage in business.

Women at court sometimes received an education, and Emperor Akbar reportedly established a

girls school at Fatehpur Sikri to provide teachers for his own daughters.

Aristocratic women often expressed their creative talents by writing poetry, painting or

playing music.

To a certain degree, these Mughal attitudes toward women may have had an impact on Indian

society.

Women were allowed to inherit land, and some even possessed zamindar rights.

Women from mercantile castes sometimes took an active role in business activities.

At the same time, however, as Muslims, the Mughals subjected women to certain restrictions

under Islamic law.

On the whole, these Mughal practices coincided with and even accentuated existing

tendencies in Indian society.

The Muslim practice of isolating women and preventing them from associating with men

outside the home (purdah) was adopted by many upper-class Hindus as a means of enhancing

their status or protecting their women from unwelcome advances by Muslims in positions of

authority.

In other ways, Hindu practices were unaffected.

The custom of sati continued to be practiced despite efforts by the Mughas to abolish it,

and child marriage (most women were betrothed before the age of ten) remained common.

Women were still instructed to obey their husbands without question and to remain chaste.

After the Treaty of Paris in 1763 ended the Seven Years' War, the British government faced

two imperial problems.

The first was the sheer cost of empire, which the British felt they could no longer carry

alone.

The second was that the defeat of the French required the British to organize a vast

expanse of new territory: all of North America east of the Mississippi, with its French

settlers and, more importantly, its Indian possessors.

The political ideas of the American colonists had largely arisen from the struggle of

seventeenth-century English aristocrats and gentry against the absolutism of the Stuart

monarchs.

The American colonists believed that the English Revolution of 1688 had established many

of their own fundamental political liberties.

The colonists claimed that, through the measures imposed from 1763 to 1776, George III

(r.1760-1820) and the British Parliament were attacking those liberties and dissolving the

bonds of moral and political allegiance that had formerly united the two peoples.

Consequently, the colonists employed a theory that had originally been developed to

justify an aristocratic rebellion in England to support their own popular revolution.

These Whig political ideas, largely derived from John Locke (1632-1704), were only a part

of the English ideological heritage that affected the Americans.

Throughout the eighteenth century they had become familiar with a series of British

political writers called the Commonwealthmen.

These writers held republican political ideas that had their intellectual roots in the

most radical thought of the Puritan revolution.

They had relentlessly criticized the government patronage and parliamentary management of

Robert Walpole (1676-1745) and his successors.

They argued that such government was corrupt and that it undermined liberty.

They regarded much parliamentary taxation as simply a means of financing political

corruption.

They also attacked standing armies as instruments of tyranny. In Great Britain this

republican political tradition had only a marginal impact.

Most Britons regarded themselves as the freest people in the world. In the colonies,

however, these radical books and pamphlets were read widely and were often accepted at

face value.

The policy of Great Britain toward America after the Treaty of Paris made many colonists

believe that the worst fears of the Commonwealthmen were coming true.

Link: Spies of the American Revolution

Historians have long held that the modern history of Europe began with two significant

transformations - the French Revolution and the Industrial Revolution.

Accordingly, the French Revolution has been portrayed as the major turning point in

European political and social history when the institutions of the "old regime" were

destroyed and a new order was created based on individual rights, representative

institutions, and a concept of loyalty to the nation rather than the monarch.

This perspective has certain limitations, however.

France was only one of a number of places in the Western world where the assumptions of

the old order were challenged.

Although some historians have used the phrase "democratic revolution" to refer to the

upheavals of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, it is probably more appropriate

to speak not of a democratic movement but of a liberal movement to extend political rights

and power to the bourgeoisie "possessing capital," people not of the aristocracy who were

literate and had become wealthy through capitalist enterprises in trade, industry, and

finance.

The years preceding and accompanying the French Revolution included attempts at reform and

revolt in the North American colonies, Britain, the Dutch Republic, some Swiss cities, and

the Austrian Netherlands.

Not all of the decadent privileges that characterized the old European regime were

destroyed in 1789, however.

The revolutionary upheaval of the era, especially in France, did create new liberal and

national political ideals, summarized in the French revolutionary slogan, "Liberty,

Equality, Fraternity," that transformed France and were then spread to other European

countries through the conquests of Napoleon.

The Scientific Revolution represents a major turning point in modern Western

civilization

.

In the Scientific Revolution, the Western world overthrew the medieval,

Ptolemaic-Aristotelian worldview and arrived at a new conception of the universe: the sun

at the center, the planets as material bodies revolving around the sun in elliptical

orbits, and an infinite rather than finite world.

With the changes in the conception of heaven came changes in the conception of earth.

The work of Bacon and Descartes left Europeans with the separation of mind and matter and

the belief that by using only reason, they could in fact understand and dominate the world

of nature.

The development of a scientific method furthered the work of scientists, and the creation

of scientific societies and learned journals spread its results.

Although traditional churches stubbornly resisted the new ideas and a few intellectuals

pointed to some inherent flaws, nothing was able to halt the replacement of the

traditional ways of thinking by new ways that created a more fundamental break with the

past than that represented by the breakup of Christian unity in the Reformation.

The Scientific Revolution forced Europeans to change their conception of themselves.

At first, some were appalled and even frightened by its implications.

Formerly, humans on earth had been at the center of the universe.

Now the earth was only a tiny planet revolving around a sun that was itself only a speck

in a boundless universe. Most people remained optimistic despite the apparent blow to

human dignity.

After all, had Newton not demonstrated that the universe was a great machine governed by

natural laws?

Newton had found one - the universal law of gravitation.

Could others not find other laws? Were there not natural laws governing every aspect of

human endeavor that could be found by the new scientific method?

Thus the Scientific Revolution leads us logically to the age of the Enlightenment of the

eighteenth century.

In 1784, the German philosopher Immanuel Kant defined the Enlightenment as "man's leaving

his self-caused immaturity."

Whereas earlier periods had been handicapped by the inability to "use one's intelligence

without the guidance of another," Kant proclaimed as the motto of the Enlightenment:

"Dare to Know! Have the courage to use your own intelligence!"

The eighteenth-century Enlightenment was a movement of intellectuals who dared to know.

They were greatly impressed with the accomplishmens of the Scientific Revolution, and when

they used the word reason - one of their favorite words - they were advocating the

application of the scientific method to an understanding of all life.

All institutions and all systems of thought were subject to the rational, scientific way

of thinking if people would only free themselves from the shackles of past, worthless

traditions, especially religious ones.

If Isaac Newton could discover the natural laws regulating the world of nature, they too

by using reason could find the laws that governed human society.

This belief in turn led them to hope that they could make progress toward a better society

than the one they had inherited.

Reason, natural law, hope, progress - these were common words in the heady atmosphere of

the eighteenth century.

scientific revolution.ppt

The Industrial Revolution initiated a quantum leap in industrial production.

New sources of energy and power, especially coal and steam, replaced wind and water to

create laborsaving machines that dramatically decreased the use of human and animal labor

and at the same time increased the level of productivity.

In turn, power machinery called for new ways of organizing human labor to maximize the

benefits and profits from the new machines; factories replaced shop and home workrooms.

Many early factories were dreadful places with difficult working conditions.

Reformers, appalled at these conditions, were especially critical of the treatment of

married women.

One reported: "We have repeatedly seen married females, in the last stage of pregnancy,

slaving from morning to night beside these never-tiring machines, and when ... they were

obliged to sit down to take a moment's ease, and being seen by the manager, were fined for

the offense."

But there were other examples of well-run factories.

William Cobbett described one in Manchester in 1830: "In this room, which is lighted in

the most convenient and beautiful manner, there were five hundred pairs of looms at work,

and five hundred persons attending those looms; and, owing to the goodness of the masters,

the whole looking healthy and well-dressed."

During the Industrial Revolution, Europe experienced a shift from a traditional,

labor-intensive economy based on farming and handicrafts to a more capital-intensive

economy based on manufacturing by machines, specialized labor, and industrial factories.

Although the Industrial Revolution took decades to spread, it was truly revolutionary in

the way it fundamentally changed Europeans, their society, and their relationship to other

peoples.

The development of large factories encouraged mass movements of people from the

countryside to urban areas where impersonal coexistence replaced the traditional intimacy

of rural life.

Higher levels of productivity led to a search for new sources of raw materials, new

consumption patterns, and a revolution in transportation that allowed raw materials and

finished products to be moved quickly around the world.

The creation of a wealthy industrial middle class and a huge industrial working class (or

proletariat) substantially transformed traditional social relationships.

In the first half of the nineteenth century, liberals had maintained that the organization

of European states along national lines would lead to a peaceful Europe based on a sense

of international fraternity.

They were very wrong.

The system of nation-states that had emerged in Europe in the second half of the

nineteenth century led not to cooperation but to competition.

Rivalries over colonial and commercial interests intensified during an era of frenzied

imperialist expansion while the division of Europe's great powers into loose alliances

(Germany, Austria, and Italy versus France, Great Britain, and Russia) only adds to the

tensions.

The series of crises that tested these alliances in the 1900's and early 1910s had left

European states with the belief that their allies were important and that their security

depended on supporting those allies, even when they took foolish risks.

The growth of nationalism in the nineteenth century had yet another serious consequence.

Not all ethnic groups had achieved the goal of nationhood.

Slavic minorities in the Balkans and the polyglot Habsburg empire, for example, still

dreamed of creating their own national states.

So did the Irish in the British Empire and the Poles in the Russian Empire.

National aspirations, however, were not the only source of internal strife at the

beginning of the twentieth century.

Socialist labor movements had grown more powerful and were increasingly inclined to use

strikes, even violent ones, to achieve their goals.

Some conservative leaders, alarmed at the increase in labor strife and class division,

even feared that European nations were on the verge of revolution.

Did these statesmen opt for war in 1914 because they believed that "prosecuting and active

foreign policy," as one leader expressed it, would smother "internal troubles"?

Some historians have argued that the desire to suppress internal disorder may have

encouraged some leaders to take the plunge into war in 1914.

The growth of large mass armies after 1900 not only heightened the existing tensions in

Europe but made it inevitable that if war did come, it would be highly destructive.

Conscription had been established as a regular practice in most Western countries before

1914 (the United States and Britain were major exceptions).

European military machines had doubled in size between 1890 and 1914.

With its 1.3 million men, the Russian army had grown to be the largest, while the French

and Germans were not far behind with 900,000 each.

The British, Italian and Austrian armies numbered between 250,000 and 500,000 soldiers

each.

Militarism, however, involved more than just large armies. As armies grew, so did the

influence of military leaders, who drew up vast and complex plans for quickly mobilizing

millions of men and enormous quantities of supplies in the event of war.

Fearful that changes in these plans would cause chaos in the armed forces, military

leaders insisted that their plans could not be altered.

In the crises during the summer of 1914, the generals' lack of flexibility forced European

political leaders to make decisions for military instead of political reasons.

Before 1914, many political leaders had become convinced that war involved so many

political and economic risks that it was not worth fighting.

Others had believed that "rational" diplomats could control any situation and prevent the

outbreak of war.

At the beginning of August 1914, both of these prewar illusions were shattered, but the

new illusions that replaced them soon proved to be equally foolish.

Europeans went to war in 1914 with remarkable enthusiasm.

Government propaganda had been successful in stirring up national antagonisms before the

war.

Now in August 1914, the urgent pleas of governments for defense against aggressors fell on

receptive ears in every belligerent nation.

Most people seemed genuinely convinced that their nation's cause was just.

A new set of illusions also fed the enthusiasm for war.

Almost everyone in August 1914 believed that the war would be over in a few weeks.

People were reminded that all European wars since 1815 had in fact ended in a matter of

weeks, conveniently ignoring the American Civil War (1861-1865), which was the "real

prototype" for World War I.

Both the soldiers who exuberantly boarded the trains for the war front in August 1914 and

the jubilant citizens who bombarded them with flowers when they departed believed that the

warriors would be home by Christmas.

German hopes for a quick end to the war rested on a military gamble.

The Schlieffen plan had called for the German army to make a vast encircling movement

through Belgium into northern France that would sweep around Paris and encircle most of

the French army.

But the German advance was halted only 20 miles from Paris at the first Battle of the

Marne (September 6-10).

The war quickly turned into a stalemate - neither the Germans nor the French could

dislodge each other from the trenches they had begun to dig for shelter.

Two lines of trenches soon extended from the English Channel to the frontiers of

Switzerland. The Western Front had become bogged down in trench warfare that kept both

sides immobilized in virtually the same positions for four years.

On the outbreak of the First World War, Serbia had an army of 360,000 men.

During 1914, the Serbian Army resisted three successive Austro-Hungarian offensives.

However it virtually exhausted the Army's manpower and it was forced to recruit men over

sixty.

The army also accepted women, including the British nurse Flora Sandes.

On the outbreak of the First World War, Flora Sandes joined an ambulance unit in Serbia on

the Eastern Front.

Although nearly forty years old, in December 1916, was promoted to the rank of

sergeant-major.

After the war, Sandes remained in the Serbian Army and had reached the rank of major by

the time she retired.

|

Arms And The Boy

Troops usually spend eight days in the front line, followed by four in the reserve.

In 1919, experimental political regimes studded the map of Europe.

The First World War had been good for the American economy.

Chiang Kai-Sheck, Roosevelt and Churchill in Cairo Egypt (Nov 25, 1943)

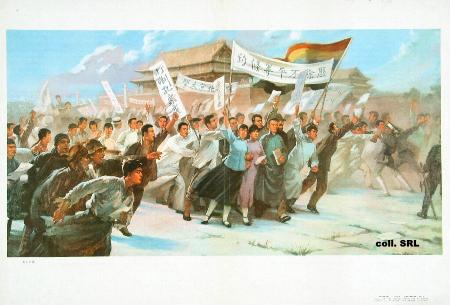

China's radicalism was intensified in the early 1960s by the outbreak of renewed war in Indochina. The Eisenhower administration had opposed the peace settlement at Geneva in 1954, which divided Vietnam temporarily into two separate regroupment zones, specifically because the provision for future national elections opened up the possibility that the entire country would come under Communist rule.

|